Health Issues of Puslinch Settlers: Part 3: Disease & Remedies In The 1800’s

This is the third in a series of articles about the health of the people of Puslinch from the earliest days of settlement to approximately 1960.

DISEASE & REMEDIES IN PUSLINCH IN THE 1800’S

By Marjorie Clark

Civil registration of deaths began in 1869 but it seems that 1871 may be the first year of thorough compliance. In that year, there was diphtheria amongst the children in the township. Three of them died: Annie Scott was 5 years old; Margaret Brown was 20 days old; and Emma Brown was 14 months. As well, there was an outbreak of scarlet fever, resulting in several deaths: John Murray was 1 year old; Catherine Murray was a few months old; John Murray was 13 years old; and James Murray was 2 years old. Consumption, as tuberculosis was then termed, was always within the populace. In 1871, James S. Buchanan, aged 20, Catherine Munro, aged 23 and John Brown, aged 6 years, died of this disease. As well as a number who died from old age, two elderly ladies, Margaret Campbell, aged 89 and Susan O’Hagan, aged 73, were listed as having died of “natural decay”. Other recorded causes were inflammation of the bowels, heart disease, paralysis, congestion of the lungs, diarrhoea, pleurisy, dysentery, inflammation of the bladder, palsy, apoplexy of the brain, inflammation of the lungs, brain cancer, inflammatory fever, liver complaint, erysipelas and puerperal mania. There were two deaths that probably caused some alarm in the community that year. David Morton, aged 55, died of cholera morbus. Peter Landon, aged 20, died of a stab wound inflicted by James Lamb.

Tuberculosis often killed people in their prime of life. Jessie Beattie wrote a touching account of the death of her grandmother in her book, “A Walk Through Yesterday”, published by McClelland & Stewart in 1976:

Grandfather paused briefly.

It was the consumption tha had struck your Grandma. She was the third of her family to be taken with it, he said. I lifted the candle and held it closer so I could better see her dear face. Our love had never faltered but now we were being put to the test.

“Jeanie”, I said to her, “What am I to do wi all thae bairns?”

She unclasped her hands and laid one cold and trembling against my cheek.

“You’ll just hae to do the best ye can, Sandy”, she said to me.

Grandpa paused again.It was only a few days after that when she left us, he said. I was broken-hearted. I did what I could for the wee ones but they needed a mother. Housekeepers, housekeepers. One spoiled their insides with too much food, another half-starved them. I was at my wit’s end. Three years of it and I had to make up my mind. There was a strong fine young woman living with her grandparents two farms away – Janet McNaughton. My thoughts kept turning to her. I had seen her once at a barn-raising at a neighbour’s farm. She was healthy looking and kind. Her manners were polite and modest. She was not looking about for attention but she had mine. I went home to think it over. A week later, I visited the relatives she lived with and made my intentions known. They gave their consent and it was arranged that I should meet and talk with her the following evening. Mind you, my lassie, I was not a cheat. I would tell the truth whatever came of it.

“My love is in the grave”, I said to her, “but I am looking for a mother for my children.”

Alexander Flemming (1826-1926) and Janet McNaughton of the Corwhin area in Puslinch had a happy marriage and two children.

At Confederation in 1867, tuberculosis was the main cause of death in Canada and it remained so until after 1900. Death was attributed to this disease in at least 90 cases of township or former township residents throughout the years. It occurred still in Puslinch as late as January 10, 1916, when Dr. James King reported to Township Council that Donald Kennedy of Badenoch was in an advanced stage of the disease and advised that he be transported to Weston Hospital or that other satisfactory arrangements be made for his care, as he would soon be too weak to move. Mr. J. Clark came to his aid in this regard and Donald Kennedy died in Puslinch on February 25th.

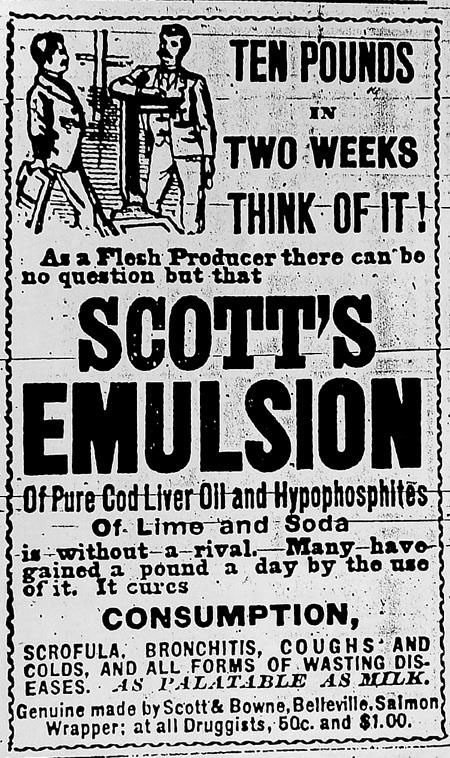

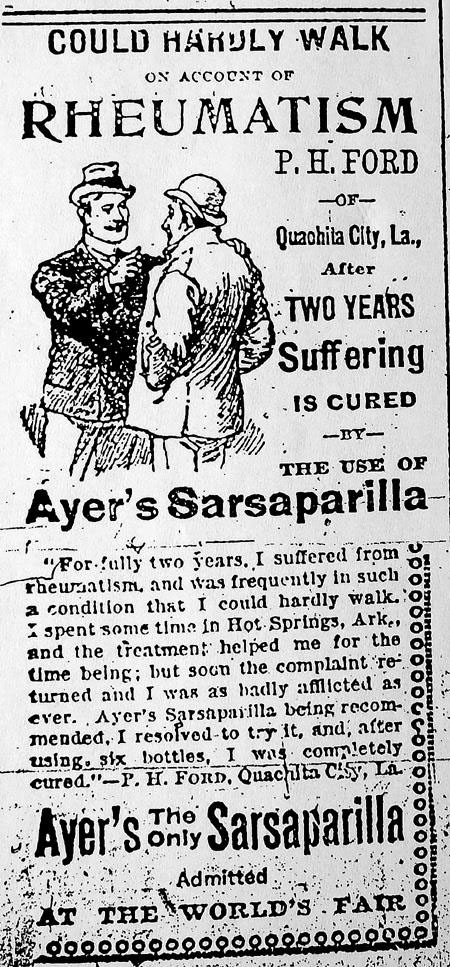

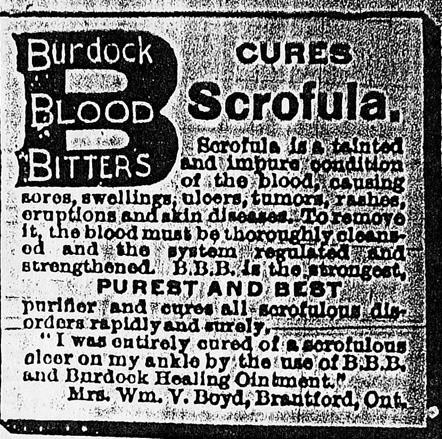

When doctors became accessible to the settler community, medicines were few. Available medicines in 1830 were mercury for syphilis and ringworm, digitalis and amyl nitrate for the heart, colchicum for gout, quinine for malaria and some plant-based purgatives. Quinine, derived from Chinchona bark was discovered in use among the South American aboriginals by the Jesuits in 1633. It was recognized in England in 1677 and was used as an early painkiller, as was alcohol and the derivative of opium, laudanum. Often, the medicine was that familiar painkiller, a shot of whiskey. Although scientists began looking at the extract of willow bark, salicylic acid, as early as 1829, it was not until 1899, that it was distributed in powder form to physicians by the Bayer Company. It was patented in pill form on Feb. 27, 1900 by German researcher, Felix Hoffman. In 1915, the miracle drug, aspirin, became available without a prescription.

Home remedies were the standard and were often written or glued into cookbooks alongside recipes. Patented medicines were widely advertised. William Watson of Arkell had a narrow escape from death on Monday, January 11, 1886, after treating his sore throat with a preparation called “Wizzard Oil”. It had the effect of choking him. A doctor in Morriston, Dr. Hilliard, opened an early version of a pharmacy in the village around 1893. It was not financially viable, however, as the populace purchased cheaper medicines from the pedlars of patent medicines, who ran wagons throughout the district.

Click any image for full size version: